I’m feeling just a bit queasy, courtesy of a Canadian cop.

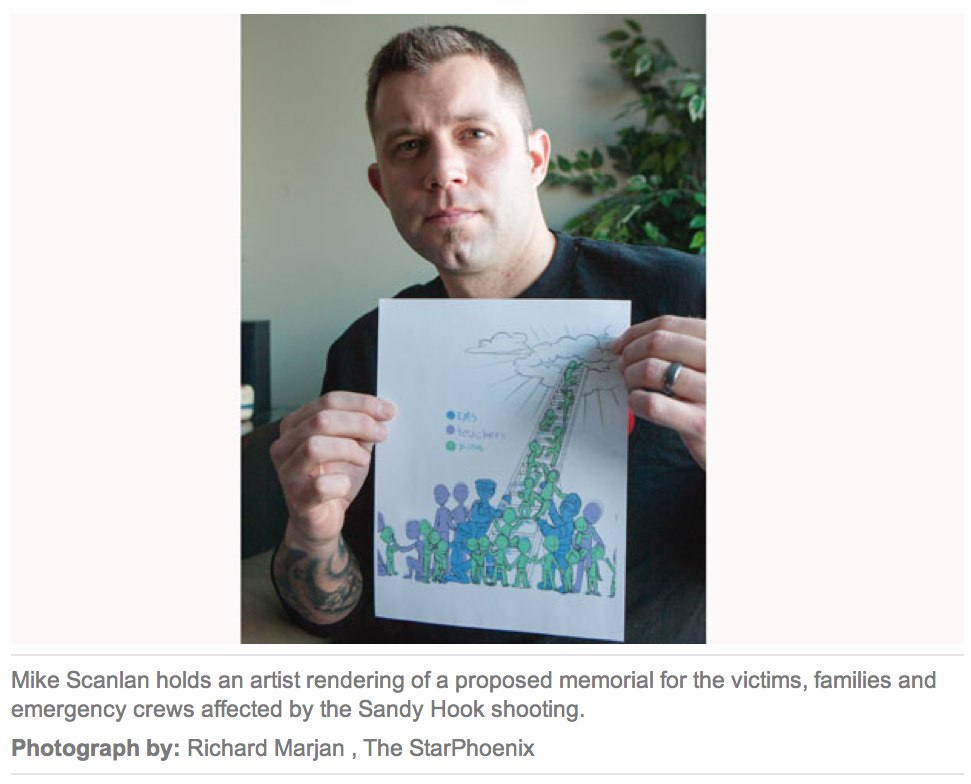

A Saskatoon police officer is working to create a massive sculpture honouring the victims and emergency workers involved in the December shooting in Newtown, Connecticut. A preliminary version of the memorial, which would be built by Saskatchewan people and shipped to Newtown, would include life-sized images of the 26 children and six Newtown teachers, as well as various emergency workers climbing a ladder into the clouds. “It’s going to take a lot of time and money, but frankly, I don’t care,” said Saskatoon Police Services Const. Mike Scanlon. “This could be us saying we care.”

It’s like a balloon made of marble or a cast-in-stone teddy bear (Newtown doesn’t even know what to do with the non-stone variations), but worse, as the proposed statue is supposed to feature the likenesses of the victims for a good stretch of eternity.

I find the whole thing maudlin and disturbing. That’s because there’s a fine line between trying to show you care and becoming an ersatz-grief fetishist. The horrible Newtown massacre was rapidly transformed into our nation’s Princess Diana moment, with an aftermath chock-full of preening public handwringing and unrestrained emoting that was almost as unbearable as the tragedy itself.

U.K. author Patrick West addressed the phenomenon in his aptly named book Conspicuous Compassion. He was interviewed by the BBC in 2004:

Describing extravagant public displays of grief for strangers as ‘grief-lite,’ Mr. West said these activities were, “undertaken as an enjoyable event, much like going to a football match or the last night of the proms. [It] is a religion for the lonely crowd that no longer subscribes to orthodox churches. Its flowers and teddies are its rites, its collective minutes’ silences its liturgy and mass. But these new bonds are phoney, ephemeral and cynical. We saw this at its most ghoulish after the demise of Diana.”

He may be on to something.

The thesis of West’s essay-length book (79 pages) is that

“such displays of empathy do not change the world for the better; they do not help the poor, diseased, dispossessed or bereaved. Our culture of ostentatious caring is about projecting your ego, and informing others what a deeply caring individual you are. It is about feeling good, not doing good, and illustrates not how altruistic we have become, but how selfish.”

In other words, the distinguishing characteristic of this affliction, otherwise cleverly known as mourning sickness and not so cleverly as grief porn, is that the public display of real or imagined grief, through cunning self-delusion, is aimed at psychologically benefiting oneself rather than the intended recipient of the good deed. It is self-PR and outright masturbation just as much as, if not more than, genuine sorrow.

If I were the parent of one of the Sandy Hook victims, I’d prefer to safeguard my own memories of my child, rather than allow her to be publicly co-opted as part of a statue I’d have to look at, or try to avoid looking at, every time I walked by.

I realize I can’t speak for the bereaved parents of Newtown.

But neither can Mr. Scanlon.

Well said, Rogier.

I have trouble understanding the urge to create memorials like this. Whatever those children were — or could have been — had nothing to do with how or why they died. I can understand that their friends and families have suffered a loss and want a memorial, but the idea of a group memorial makes me very uncomfortable. The only thing that links their deaths together is that they were all killed by the same guy. So when you create a group memorial, are you creating a memorial for their loss, or are you creating a monument to their killer?

Laura Agustin pointed out some time ago that the same kind of “ostentatious caring” is behind the popularity of “sex trafficking” hysteria: http://www.lauraagustin.com/have-fun-take-a-tour-to-meet-victims-of-sex-trafficking-learn-to-be-a-saviour

Here’s a recent example of one of these lugubrious displays, from Atlanta: http://www.11alive.com/news/article/270773/3/Passion-2013-tackles-sex-trafficking-slavery As West points out, this isn’t about the victims of tragedy, whether real (as at Sandy Hook) or imaginary (as in “sex trafficking”); it’s about the people who have big rallies and go on TV to show how much they “care”.

Seems like the same motivation behind [pick a color] ribbon campaigns, too.